From CUNY Academic Commons

Contents |

Create a social media policy

Social media is key to 21st century communication with library users, and enables the academic library to pursue its mission and goals online, while promoting library resources and services. As Johnson and Burclaff note in their 2013 ACRL conference paper, “Making Social Media Meaningful: Connecting Missions and Policies”, 94% of academic libraries have a social media presence, mainly on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, but only 2% of those surveyed have a library-specific policy for social media (402). They also stress the importance of linking the academic library social media policy to the library’s mission statement, stating, “Mission-based goals and actions are particularly valuable in areas of rapid change, like social media… The library mission should drive the library’s activities and should therefore be present in these guiding policies.” (404)

Implementing a social media policy will streamline responsibility for the management of various platforms and provide guidelines for posts and interactions online with library patrons and the public. A written policy will also define the purpose of engaging in social media, moving past what content you share and how you share it to why the library is using social media at all. In his blog post, “Why does my library use social media?“, Brian Mathews writes, “It’s not about promoting the library, this is about building brand loyalty. It’s not about posting library news for students, but about building an ambassadors program, a network of friends and allies. The goal is a transition patrons from being library users to library advocates.”

Examples of academic library-specific policies

Many academic libraries rely upon the social media policy for their university, but there are several organizations that have made the effort to design a policy that reflects the needs of the library.

- Drexel University Queen Lane Library Social Media Policy

- all exchanges on social media are considered extensions of Circulation/Reference Desk interactions, staff members respond to all comments and messages

- Oregon State University Libraries Social Media Policy

- states that the library reserves the right to use comments and stories shared/posted by users in promotional materials for the library

- offers a web form for non-library individuals to submit ideas or suggestions for posts

- University of Baltimore Langsdale Library Social Media Policy

- asks librarians and library staff to consider the ALA Code of Ethics when using social media

- Walden University Library Social Networking Policy

- emphasizes that by ‘liking’ or ‘friending’ the library users agree to receive communication via a particular social media channel

- Washington State University Libraries Social Media Policy

- assigns a responsible administrator to each social media account

Key themes

Johnson and Burclaff identify the following themes as key to both a mission statement and a social media policy for the academic library:

- Encourages knowledge creation

- Improves institutional outcomes

- Integrates print and electronic resources

- Provides access

- Provides space

- Supports curriculum

- Teaches information skills

Reflection question

- Why does your library use social media at all?

| Library | Why we use social media |

|---|---|

| Brooklyn College Library | edit me! |

| Hunter College Library | edit me! |

| Queens College Library | edit me! |

| add your library! | edit me! |

Determine how social media will be used

There are many social networks to choose from, with Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter being the most popular platforms used by academic libraries (Johnson and Burclaff 2013, 402). According to the Summer 2013 issue of ALA Tips and Trends, academic libraries use these three platforms, as well as blogs, for outreach and to share information about events, services, or resources (2). The authors, Sheila Stoeckel and Caroline Sinkinson, also identify ways that librarians are using social media channels as tools for instruction, particularly online collaboration, curation and sharing, and practicing inquiry (2-3).

Examples of how academic libraries use social media

- Yale University Library ~6,500 likes, posts events, news, links, pictures, and highlights special collection:

- 10/26/2013 After the Red Sox won game 1 of the 2013 World Series, the library shared a photo of the team from their special collection, and mentioned another item in their possession – the first known printed account of baseball.

- 10/28/2013 The library posted the image of a flyer for a talk taking place in a library space, cosponsored by the library and the campus health department, focused on fact, fiction, and folklore related to the prostate.

- NYU Libraries ~1,500 likes, posts events, news, links, and points users toward library resources and authoritative sources of information:

- 11/05/2013 The library posted an image of “The Credible Hulk” with a link to their libguide on citation.

- 09/02/2013 A post celebrating NYU library patrons access to BrowZine links to a libguide explaining how to access the service.

- Columbia University Libraries ~1,500 followers, news, events, announcements, and links to timely content:

- 09/19/2013 The library tweeted a picture from the archives of students hanging out and identified the present-day name of the location.

- 07/24/2013 A tweet promoting a Publisher’s Weekly article that quotes a Columbia librarian links to the article, the publication, and the librarian’s twitter handle.

- Northwestern University Library ~2,500 followers, responds to questions and comments promptly, having conversations with users, and highlights unique library details – like to which floor the coffee cart is heading:

- 09/03/2013 The response to a directional question about printing at the library includes a link to their libguide on the topic.

- 09/24/2013 The library promptly responds to a patron criticizing the library facility.

YouTube

- University of North Carolina Library ~50 subscribers, 25 videos, video tours of the website, instructional videos, library promotion, past events and conference speakers:

- A 3 minute video explaining how to use the library’s mobile web site has 750+ views.

- A UNC librarian collaborated with peers at two other academic libraries on an animated video that explains the nuances of the Georgia State University Copyright case, the video has 80+ views.

- Harvard College Library: ~100 subscribers, 20 videos, includes videos for library instruction, and marketing

- 03/25/2010 A video about how to locate e-resources using keywords and subjects has 600+ views.

- 01/07/2011 A fifth year graduate student has gotten 1,600+ views for a video that explains the top ten things graduate students should know about using the academic library.

- UCLA Powell Library ~1,500 followers, current and historic images of the library, pictures of patrons using the facility, covers of books in the library’s collection, event flyers

- 10/07/2013 The library posted a picture of a student dancer doing a split in the stacks while reaching for a book.

- 08/08/2013 Using the hashtag “throwbackthursday” a picture from 1968, of students frolicking in a fountain on campus, is posted with the explanation that a grate was placed in the location to stop that type of activity.

- Rutgers University Libraries

- 04/11/2013 Using Instagram as a platform for interacting with their users, the library advertised a contest for photos of favorite study spots in the library (second place photo).

- 03/29/2013 The library posted a picture of the control panel for their new compact shelving, and invited their followers to come check it out.

Tumblr

- Columbia College Library: posts book covers which link back to the item record in their library catalog

- Montana State University: historical photos from archive, pictures of library books being repaired, book covers,

Flickr

- American University in Cairo used this platform to teach database concepts (this is a link to the full text article on Eric)

- Cornell University Library holds a contest where students are encouraged to remix historic photo images from their Flickr stream, and post their artistic creations on Flickr, with the tag ‘CULRemix’

Reflection question

- How does your library use social media networks?

| Library | How we use social media |

|---|---|

| Brooklyn College Library | edit me! |

| Hunter College Library | edit me! |

| Queens College Library | edit me! |

| add your library! | edit me! |

Provide content that facilitates literacy

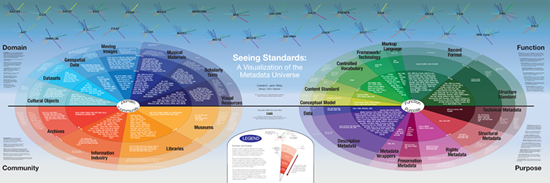

Information literacy is a familiar term, and, as noted above, it is a theme in academic library mission statements. However, there are several new definitions for literacy that have emerged related to the use of web 2.0 functions and social media channels.

New types of literacy

The main thrust of the new terminology for types of literacy has to do with web 2.0 functionality, and users learning in the process of making or contributing knowledge – process over product. According to David Lee King, it is important to ensure that “everything you do includes some type of “ask”… make sure to provide customers with some next steps, and actually invite them to take that next step”. In order to facilitate this, academic libraries can let users contribute to an appropriate knowledge base, setting up opportunities on social media platforms for patrons to learn through doing – through means such as clicking on links, uploading content, commenting on items, and tagging digital objects. This is in line with the constructivist teaching theory, as Greg Bobish discusses in his article “Participation and Pedagogy: Connecting the Social Web to ACRL Learning Outcomes“, where he states, “Instruction designed to take advantage of the tools’ capabilities on their own terms, however, will prepare students to directly apply information literacy skills as these technologies are increasingly encountered in daily life.” Two current terms being used to describe this learning process and the relevant skill set are the following:

- Metaliteracy

- “A unified and comprehensive approach to learning that encourages the production and sharing of original and repurposed information in participatory environments” – Tom Mackey, Trudi Jacobson, Jenna Hecker, Tor Loney, and Nicola Allain

- “Moves beyond an exclusively skills-based approach to information and emphasizes collaboration in the development and distribution of original content in synchronous and asynchronous online environments” – Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson

- Transliteracy

- “The ability to read, write and interact across a range of platforms, tools and media from signing and orality through handwriting, print, TV, radio and film, to digital social networks” – Sue Thomas, Chris Joseph, Jess Laccetti, Bruce Mason, Simon Mills, Simon Perril, and Kate Pullinger

- “It analyzes the relationship between people and technology, most specifically social networking, but is fluid enough to not be tied to any particular technology.” – Tom Ipri

Metaliterate ideas for social media interactions

- Let patrons assist in the creation of knowledge bases

- Let users tag items in the library catalog

- Provide special collections photographs on a platform where users can comment

- Have users micro-blog research questions and thesis statements

- Ask students to use a social bookmarking tool to aggregate resources, tagging them as primary or secondary, along with other metadata

- Create a wiki for popular research topics, where users can contribute research questions, get ideas on how to narrow their focus, and add links to relevant blogs and podcasts

- Create a wiki for trending topics, where students can add citations for primary sources and links to raw data

- Have students create a blog post (YouTube playlist) where they annotate video, audio, and/or images

- After completing an assignment, ask students to blog about the process – where they found information, obstacles they encountered, and the quality or their sources

- Have students compare RSS feeds for scholarly blogs to search alerts in subscription databases

- Ask students to take pictures of where they found resources in different parts of the library and tag them with call numbers

- Get students to post a source in their Facebook status, so that others can ‘like’ it and discuss it in the comment section

- Have students pose their research questions to Facebook or Twitter

- Release content under the Creative Commons license and ask students to remix it

Reflection question

- What does your library do with social media that enables metaliteracy?

| Library | What we do on social media that enables metaliteracy |

|---|---|

| Brooklyn College Library | edit me! |

| Hunter College Library | edit me! |

| Queens College Library | edit me! |

| add your library! | edit me! |

Checklist for social media posts

Ann Handley, of Mashable, offers these tips for posting to Facebook, Twitter, and blogs:

- Keep the Goal of Your Post Top of Mind – WHY are you posting this??

- Write Compelling Headlines – precise and/or funny

- Lead with the Good Stuff – give a solid overview in first phrase

- Make Every Word Count – do NOT abbreviate

- Keep it simple – less is more, link to the full story

- Provide context – use keywords and hashtags

- Graphics expand the story – visually describe your headline, scan an image or take a picture if necessary

- People make things interesting – use a conversational tone

- Consider the reader – respect your audience and think twice before you post

Finally, to take your social media post from transliterate to metaliterate, make sure to provide next steps (a question or instructions)!

Brooklyn College Library meeting notes

December 4, 2013 – “Let’s Get Social”

- What makes sense for us to be doing?

- posts delivered on set days in certain topical areas, for example Science Fridays, Search Smart Saturdays, Tech Tuesdays

- schedule of things that are posted every term, set the timing with Hootsuite

- target specific audiences through social media?

- use sub-lists on Facebook to organize who sees your posts

- create lots of Facebook pages, for each department or librarian

- “being in the soup of it all has value”

- Social currency

- leave our page being “in the know”

- How do we want to proceed?

- We need conversations, and procedures

- We need an implementation subgroup

- Who are our followers/students?

- What are our procedures for posting? for removing posts?

- Things related to information literacy should be posted by librarians – what about interns, CA’s, AIT staff?

- Are we vetting every post? Bringing them to a group to discuss?

- Set up an ad-hoc social media implementation committee, experiment with someone else’s social media policy, and practice with a pilot program – then review?

- Miriam, Mariana, Nick, Courtney, Neil, Beth, Howard, (Deimosa): committee!

Resources

Bobish, G. (2011). Participation and Pedagogy: Connecting the Social Web to ACRL Learning Outcomes. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(1), 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2010.10.007

Handley, A. (2013, October 9). Social Media Writing Tips. The Ohio State University – Section of Communications and Technology. Retrieved from http://cfaes.osu.edu/commtech/sites/drupal-ct.web/files/resources/files/Social%20Media%20Writing%20Tips.pdf Ipri, T. (2010). Introducing transliteracy: What does it mean to academic libraries? College & Research Libraries News, 71(10), 532–567.

Johnson, C., & Burclaff, N. (2013b). Making Social Media Meaningful: Connecting Missions and Policies. In Imagine, Innovate, Inspire (pp. 399–405). Indianapolis, IN: American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2013/papers/JohnsonBurclaff_Making.pdf

King, D. L. (2013, January 08). Five Tips to Reshape your Social Media Plan in 2013. Retrieved from http://www.davidleeking.com/2013/01/08/five-tips-to-reshape-your-social-media-plan-in-2013/

Mackey, T., & Jacobson, T. E. (2013, April 23). ACRL 2013 Metaliteracy. Education. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/tmackey/acrl-2013

Mackey, T., Jacobson, T., Hecker, J., Loney, T., & Allain, N. (2013). What is Metaliteracy. Metaliteracy MOOC. MOOC. Retrieved November 6, 2013, from http://metaliteracy.cdlprojects.com/what.htm

Mackey, T. R., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011). Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries, 72(1), 62–78.

Mathews, B. (2011, July 6). Why does my library use social media? The Ubiquitous Librarian. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/blognetwork/theubiquitouslibrarian/2011/07/06/why-does-my-library-use-social-media/

Stoeckel, S., & Sinkinson, C. (2013). Tips and Trends. Instruction, (Summer). Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/aboutacrl/directoryofleadership/sections/is/iswebsite/projpubs/tipsandtrends/2013summer.pdf

Thomas, S., Joseph, C., Laccetti, J., Mason, B., Mills, S., Perril, S., & Pullinger, K. (2007). Transliteracy: Crossing divides. First Monday, 12(12). Retrieved from http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2060

Witek, D. (2013, April 18). “I Found it on Facebook”: Social Media and the ACRL Information Lit… Business & Mgmt. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/donnarosemary/i-found-it-on-facebook